Politicians, conquerors, settlers, and those in power often rename places to leave a mark: a way of saying, We were here; we have pissed; we have marked this territory. One can only wonder how many names a place, trampled by many feet, has worn through the ages, through different waves of change, sudden or gradual.

But have you noticed that people who seek to get closer to nature often do the opposite?

Instead of renaming, they try to learn the names already given. They listen. They trace etymologies. They pay attention to what the land and its people have long known.

Recently, we read this in Marginlands by Arati Kumar-Rao. She shares the story of pastoralists in the Thar Desert, who have dozens of names for clouds and the readings they take from them. Before that, there was Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks, a quiet manifesto on the poetry of place names and the urgency of recovering a vanishing natural lexicon.

They are among the few who have written books. Many others pass this knowledge down orally, in fragments, in smaller circles. You only have to look carefully. On blogs, in local archives, to start unearthing these lost words.

Glossary of Things Past

Take, for instance, the Oral History Narmada project, which has preserved a beautiful, fading list of fish names once found in the river before the dam altered its flow. Rehmat and Dilip Zelve of Manthan Adhyayan Kendra compiled it:

https://oralhistorynarmada.in/the-fish-variety-in-the-river-narmadaOr pore over this list of toponyms across Karnataka, patiently collected by Pushpa and Siddeshwar on their blog Karnataka Travel:

https://karnatakatravel.blogspot.com/2017/04/toponymy-across-karnataka.html

Each name, each way of naming, opens a door. It reveals a logic, an ecology, a worldview. Often, it gestures to a world far removed from our screens and the imposed language of urban planners and builder-politicians who name and act on our behalf: NAINA, Mumbai 3.0, NOIDA, Cyberabad. MIDCs, SEEPZ. These are not names of memory, not yet. They are names of marketing and a reflection of ourselves.

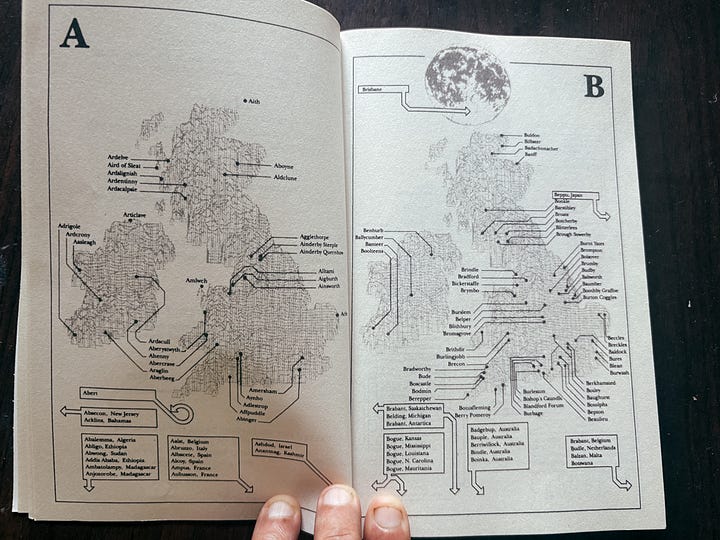

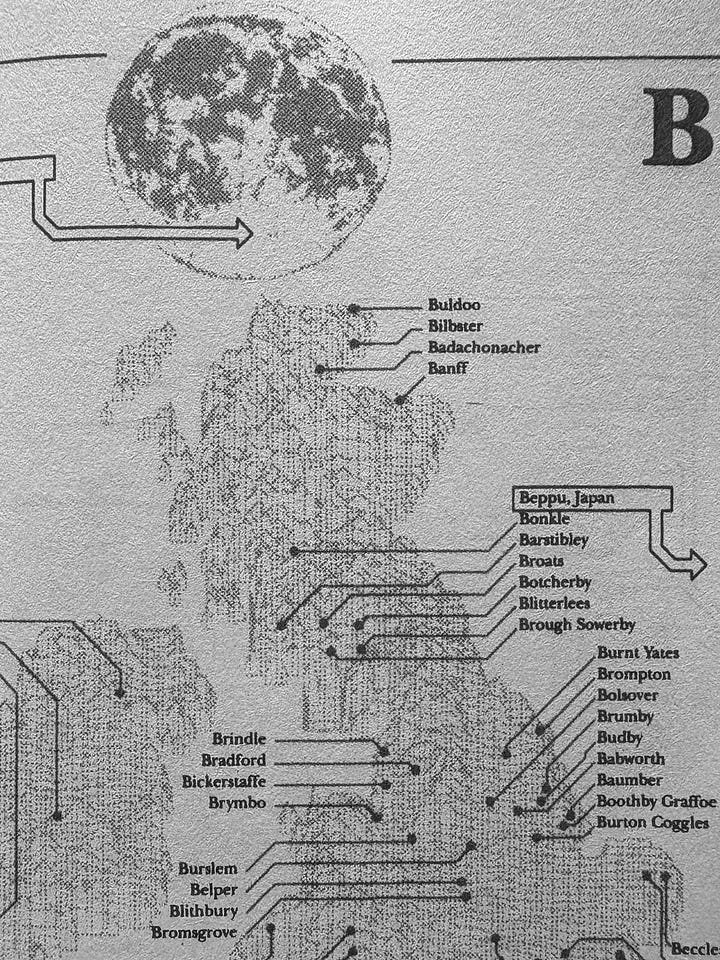

After reading an earlier post I’d written on subsurface memory, a school friend, Srikanth V, sent me a copy of The Deeper Meaning of Liff by Douglas Adams and John Lloyd, which had an interesting section called Maps. It’s a parody: real toponyms (mostly British) repurposed as comic definitions for everyday experiences that don’t yet have names. The maps inside are wilfully inaccurate. But beneath the humour is a subtle point, that naming is a creative act. A form of noticing, even when it’s absurd.

Yet there’s a difference between Douglas Adamish naming and the deep-rooted names that emerge from a lived relationship with place. The older toponyms from agrarian, indigenous, or place-bound cultures carry layers of memory, ecology, and belonging.

The people mentioned above, along with others who quietly maintain such practices, view naming as a means to cherish and protect the natural world. To speak the names of rivers, rocks, hills, trees, winds, fish, and communities now lost is a form of love. And perhaps, resistance.

Macfarlane’s work, especially, responds to the slow erasure of this vocabulary. When children’s dictionaries began dropping words like acorn, bluebell, and otter in favour of iykyk, broadband, cut-and-paste, and chatroom, he saw it for what it was: a shift in worldview. A loss of intimacy with the natural world. A kind of forgetting.

But remembering is possible. Understanding names and the knowledge they convey re-enchants the world. The Narmada fish list shows how language and loss are intertwined. Toponymy, then, becomes a form of resistance, a quiet defiance against the tsunami of greed that troubles landscapes and our futures, not to mention other species.

Their observations whisper a deeper concern: when we lose the shared language of nature, we lose a part of ourselves.

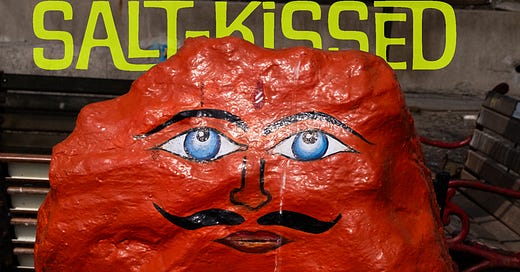

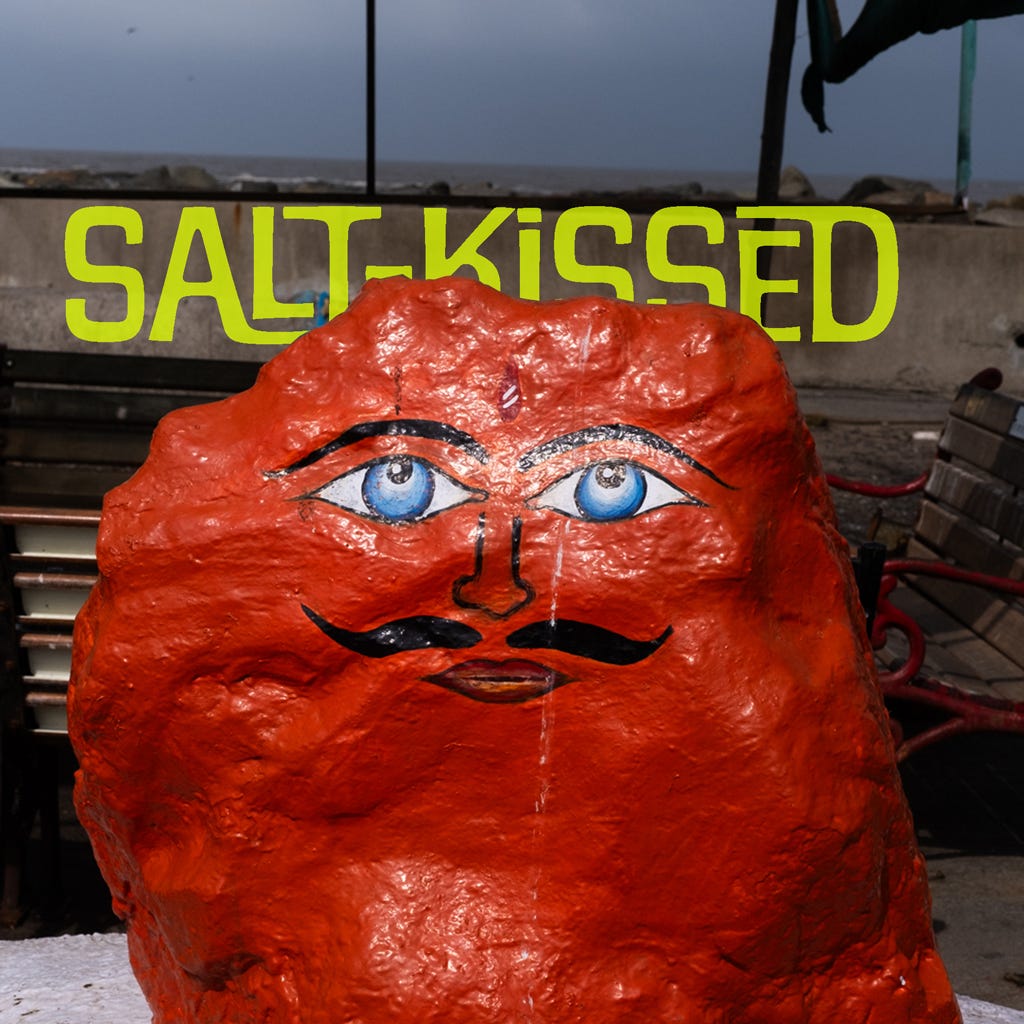

This finally brings us to today’s photo essay from the salt-kissed village of Dhanda adjoining Khar and south of Juhu.

Zuem. Juem. Juhu. Danda.

Zuem, also spelt as Juvem or Juhu along the Konkan and Goa coast, refers to a slender, elongated island or peninsula found along the western coast of India.

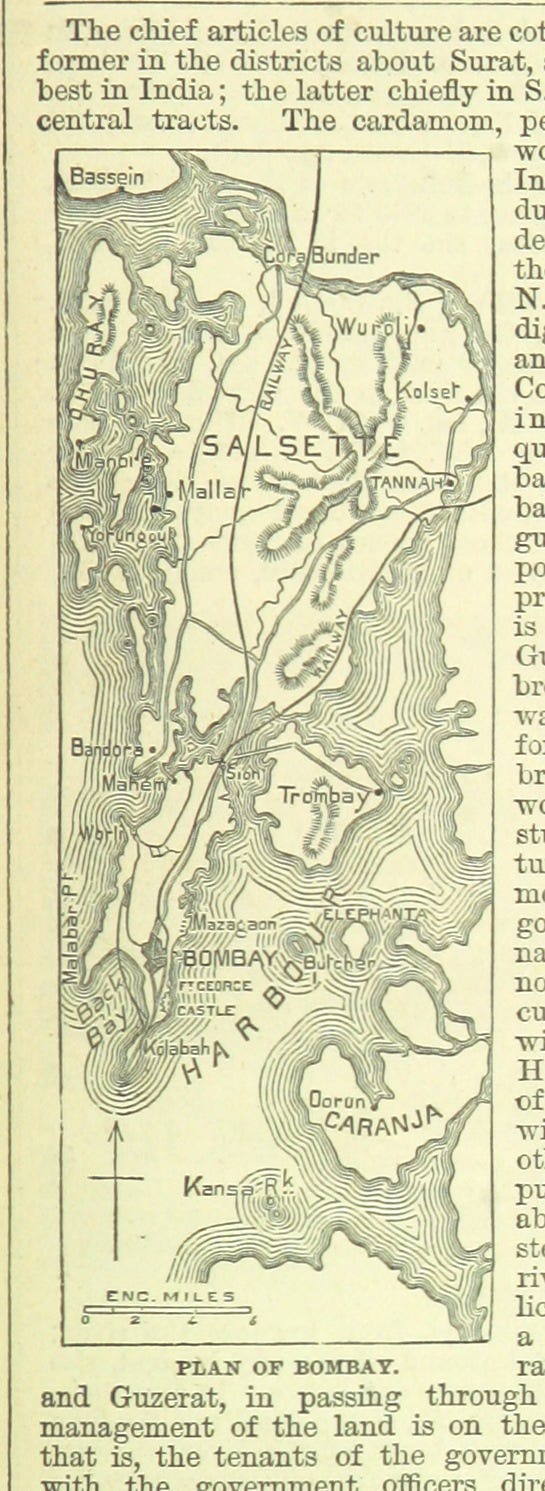

The original Danda is the sandbar located above Bandora, as shown in the following map.

These landforms were typically shaped by coastal or riverine processes such as sandbar formation, tidal flats, or land reclamation, resulting in narrow strips of land parallel to the shoreline or riverbank.

Danda (or Dhanda) in Marathi coastal toponyms refers to a sandbar, spit, or narrow strip of land, often formed by the action of tides and currents, that projects into the sea or separates a creek from the open ocean. You would encounter Danda not only in Khar but also in Rev near Alibag, Madh, Dapoli, Arnala, and other places.

Zuem. Juem. Juhu. Danda. These aren’t just place names. They are salt-kissed fragments from older geographies. We live in a time when names are engineered, sold, and packaged, where place becomes product. Where cities change their names every few years. But the older names remain—in old maps, waiting to be seen online; in an old fisherman’s song or voice; in a sandbar that is now poured over by concrete; and sometimes, in photographs.

Can photographs, like names, carry memory?

They hold traces of salt, light, and silence. They help us remember what we risk forgetting. So here are some pictures from the Salt-Kissed Danda, still stubbornly connected to the memory worlds that came before Mumbai.

This following shrine is older and on the southern edge of the Danda village bordering Chuim Village of Bandra.

Adjacent to the temple is the large Danda fish market, catering to the affluent residents of Bandra and Khar.

The space between Danda and Chuim was a vast expanse of land where Bombil, ribbonfish, and other fish were dried. Over the decades, the space has shrunk along with the catch of Bombil along our polluted coast.

On the edge of these grounds are the graves of members of the Gujarati community who reside in Khar. Once surrounded by breathing space, the road, parked vehicles, and new construction are gradually encroaching on them.

Translation:

Local/Resident Shri Bapu

Died: Vikram Samvat 2035 (Sud Pancham, Sunday)

Date: 18-01-1979A memory of a living soul.

Dedicated to the reverence of culture.Also Kisan Parmar, who passed away in 1979.

The Northern Boundary of the Danda.

In the following image, you can see the northern border of the old sandbar. This inlet now drains the large Govindnagar and other settlements that occupy the former wetlands that existed here.

Danda is one of the few villages where hockey is a popular Sunday morning game. That old national game of India no one plays anymore in the age of WWE-style cricket and its large betting ecosystem.

The village still has a sizable population of traditional fisherfolk and motor boats.

The Future Beach

The shifting sands of the sandbar are constantly expanding, not by the action of the waves, tides and wind but with cement, stones and powdered rock that we now use instead of sand for our buildings.

Just off the beach and in the soft sand is probably the smallest well you will see in Mumbai with the shallowest of water tables.

Not sure if the water is potable because the village seems to prefer packaged water for drinking.

I have only skimmed the surface of this wonderful sandbar of a village, and hopefully will be going back for more salt-kissed images.

But for now, that’s all, folks!

"Zuem, also spelt as Juvem or Juhu along the Konkan and Goa coast, refers to a slender, elongated island or peninsula found along the western coast.." something to learn today. Wow!

It's time for a book Gopal. Your work is way too valuable and stunning to be left for an ephemeral blog.