The Tastemakers of Hate in India

Kunal Purohit talks about his book H-POP: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars at Swapbook's Twice Told

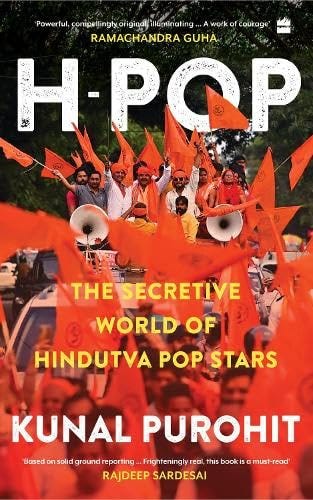

Journalist Kunal Purohit has a new book called H-POP: The Secretive World of Hindutva Popstars. The book follows three main people – a singer, a poet, and a publisher, all of whom use a mix of YouTube and platforms/stages provided by Hindutva political parties to promote the Hindutva ideology, especially its rabid Islamophobia and hatred for people like Mahatma Gandhi. They are all rock stars in their own right, with millions of likes and views from the Hindi-speaking world.

The content they produce seems to be the noise that fills the heads of millions of Hindi speakers who form a large section of the Indian population and reside in the North, Central and North Western parts of India.

Last weekend, Swapbook Mumbai, a group of readers from Mumbai that I am part of, invited Kunal Purohit to our monthly meet-up with writers called Twice-Told to talk about his book.

Listen to what he has to say, or below the videos (and images) are the transcripts of the videos for those who prefer to read.

Questions from the audience:

Videos shot by

Venue: MCubed Library, Bandra, Mumbai.

Here are a few images from the interaction:

Transcripts of the videos:

Note: It has been slightly edited for easier comprehension

Video 1:

Kunal: One element of all of the pop culture that I talk about in the book is that you know, these characters and artists also have a sense of organic popularity.

You know, they're not people who are contrary to what one would imagine or contrary to what one would suspect they're not; they're not people who are, you know, sort of created by the Hindu right-wing or funded and some told to grow by the BJP or the SS or any of these organisations. Kavi Singh (The singer) is the perfect example of the story of Kavi and how she, yeah, you know.

She is someone who delivers cosmetic treatments. She is, you know, a beautician, working at a beauty parlour in a small town in Haryana. And then one day, she's cooking food and humming a song like some of us do. And you know, her father, who's a Haryanvi singer, he happens to catch her in that moment, and he says, and you know, the next thing we know is, is, is the following day Kav is in the studio recording a song just to see if she can sing or no. And then modern technology, Gopal, is beautiful because it can also make people like me singers. You know, what essentially happens is she goes into the studio and then auto-tune, and a bunch of other technologies help her achieve that sort of perfect melody in the voice, and she becomes a singer, right? So, no external force is driving her to become a singer. No RSS, the BJP, or the VHP is coming and saying you should become a singer.

What happens is there's the Pulwama terror attack that occurred in 2019 (just before the last general election). This is, and she's just discovered that there's a singer inside her. You know, in the days after the terror attack, we're all sort of angry, we're outraged, we're confused, we're wondering, you know, how this could happen, especially under the watch of a government that sort of prides itself in being the custodians and the guardians of the country, and we're asking questions about who could have done this, right? But Kavi has a very different take on it.

She gets a poem written by a fellow poet, and the poem does not ask any of these questions. The poem is essentially saying, you know, leave Pakistan, leave the terrorists, leave all of these people aside.

The people who've created this situation and the people who carried out this terror attack are essentially the Muslims living amongst us. That is the rhetoric the song employs. Right. And at this point, there is no RSS, no VHP, nothing at all. And she decides to go ahead with a song, which is how her first song comes into being. And then that song catapults her into, you know, a different league of fame where overnight she becomes, she becomes a sensation of sorts, you know, people are lip-syncing this on YouTube, people are lip-syncing to her songs, people are making their cover versions of it, and so forth.

So, this is a very organic birth of Kavi Singh, the artist, which is why, you know, I didn't want to fall into the liberal trap of blaming everything on the Hindu right-wing or the BJP or the RSS or YouTube or YouTube.

I think it's essential for us to understand that there are various ways in which the Hindu pop culture is also growing, and like Kavi's song's popularity tells you, there's a vast audience among us who enjoy this kind of pop culture, who want and who want to consume this kind of pop culture, right? So, as I said, the lazy way out would be to blame it on the organised Hindu right wing. Still, I've chosen not sort of to do that and look at the more organic ways in which they've also grown. Of course, as you know, on the way in the journey, getting some help from the BJP and the RSS and its many affiliate organisations, where one sees that as soon as some of these pop stars become popular, you know, these organisations start sort of giving them platforms and saying, oh okay, you know, clearly you're doing well.

Why don't you come and perform at our rallies? You know, and why don't you come and address our troops? Um, that is the symbiosis between these two worlds.

Question: Who are the fans and listeners?

You also mention that people might not follow Kavi or other creators of many of these songs, but people are making remixes of it, or people are what you call DJs are remixing them and making them popular. So, how does this economy work?

Like who are these people? I assume some fans are doing their version of the fan thing. So, how does this entire, because here we don't get to meet these people, but you have seen them, who are these people?

Kunal:

So, what's fascinating about this sort of Hindutva pop culture is that you know, these songs are not meant for one occasion alone, so they can be songs that, you know, as I said, you can play while you're in a public bus, which is what happens immensely in places like UP and Jharkhand, where I've seen this happen. They can be songs that can be your caller tunes; they can be your ringtones. Incidentally, when I first discovered Hindu pop, the driver who was ferrying me around was one Bajrang Dal worker in Jharkhand, and he was the driver, and his song was, you know, this sort of anthem of Hindu pop. It was a song called "Ar Jai Shri Ram" and so forth. So, this was his caller tune, and I would wake up every day, calling him up and sort of listening to the song at the start of my day. So, that's one version of the song, but a big bulk of where these songs also get utilised are these massive processions, Gopal. You know, which are these Ram Nami processions that happen in places like Jharkhand especially, you know, Jharkhand and Bihar have a history of massive Ram Nami processions consisting of anywhere between tens and thousands of people to hundreds of thousands of people also. And I'll show you some videos if you can. Still, it's just that sort of scale of the processions where these songs then get employed because this is really what keeps the crowds mobilised, keeps them roused with the feelings of Hindu, um, the feelings of, you know, sort of having another to blame, uh, creating a victim out of minorities, creating a victim out of critics, and so that is a big arena in which Hindu pop performs, uh, and sort of I would say that is one big function of Hindutva, to keep all of these crowds going, to give you an example, one of the songs that is very popular in this world is this song that is often played in front of mosques in these Ram Nami processions, right? Typically what would happen is that these processions would

During these processions, they would snake through the towns and stop right in front of the mosque. This was the moment when they would play some of the most potent Hindu pop songs. One stands out as it plays outside the mosque. If you're unaware, it's also a form of Shakti Puja in places like these. The processions carry swords, sticks, and rods with them. Instead of waving them while crossing the town, especially in front of the mosque, they play this song. This tends to arouse the participants, creating a moment where an incident could occur. It could lead to a riot or a clash, or simply escalate tensions, which unfortunately often go unreported in smaller towns.

This highlights the primary function of some of these songs.

The book's first half focuses on the singer, followed by the poet and then the publisher, discussing myth-making. The essence of Hinduism portrayed here differs from the traditional one with castes, reflecting a shift seen since the early 20th century. Hindu nationalist movements have fostered myth creation around various religions, perceiving Hindus as constantly under threat, be it from farmers, students, or external forces like Netflix and Amazon.

The publisher, Sandeep, sees himself as a cultural warrior, fighting against Western influences infiltrating Indian values. He believes platforms like Netflix promote ideas contrary to traditional Indian family values, advocating for Hindu-friendly content instead. This emphasis on creating enemies serves to mobilise Hindus by perpetuating a sense of threat to their identity.

Regarding the electoral process, while there may be ties to political parties, the phenomenon of Hindu pop culture transcends mere electoral gains. For instance, the viral success of a song before the UP elections wasn't orchestrated by a political party but gained attention due to its popularity. Subsequently, political parties may leverage such cultural trends, but the genesis lies outside their influence.

Regarding gender dynamics, women like Kavi, who enter this male-dominated space, often adopt masculine personas to fit in. Kavi, for example, dresses like Narendra Modi and feels empowered when embodying a manly image. This underscores the complexity of gender roles within this cultural context, where women sometimes have to adopt masculine traits to navigate the space effectively.

Part 2: Question and Answers.

Question from Vedant:

Social media, YouTube, and everything like that are noticeable not just in India but other countries, like the US, with their Christian streaming channels and everything. I want to know how they are so good at it, but then the left wing can't capitalise on it?

Kunal:

Great question. It does trouble me sometimes, but I think, look, um, to hate is always a sexier ideology, pardon my language. Still, it's sexier to sort of rouse people against something, especially when it comes to hate, because I think what you're doing is you're appealing to emotions like anger, you are appealing to emotions like fear, you're trying to rouse those emotions out of you. In contrast, the counter to it is don't fall for hate, correct, or try and preach Brotherhood, try and preach Harmony, which is in no way, you know, sort of as rousing a cause as well sometimes. So, that is one aspect of it, and this is, you know, classic fascism as well if you go back. It's always easier to sort of push for things, push for causes that intrinsically involve hate, which requires fear because people are more likely to take it up. So, that is, for me, a straightforward example of why this kind of content sells because essentially, as I said, what they're trying to do is paint this image that this is the last refuge of Hindus in the world. They keep saying this, they say that Hindus are a global minority, this is the last refuge left, as if Hindus from across the world have all sort of come here and occupied India, and you know, if we don't take action, then Hindus will be wiped off. So, somewhere, what happens is that we all have carried a lot of this baggage from the start, even when we were kids, you know, even when we were in school and things like that. I remember growing up in Bombay back then in the shadow of the 92-93 riots, so some of these myths were very prevalent at that point, and then when you carry these myths, all that it sometimes takes is one stray example here and there of confirmation and you say yes, you know, this is the myth that I've heard about, so that sort of becomes a thing that you then hold onto all your life, and that is the moments that they also try and capitalise on because if you see if there's one example of a Muslim guy killing a Hindu girl, which happened in Shradha Waikar was an interesting case, they was, you know, the whole ecosystem was so quick to keep churning out content which would reiterate their religious identities, except that after that there were so many different cases where, you know, sometimes both of them were Hindus, sometimes the guy was Hindu, the girl was a Muslim, and so on, but you wouldn't think of those at all, you wouldn't even remember that. So, I think the ecosystem also got very good at understanding what the messaging is and understanding how to convey that messaging very effectively, which I think the other side, the left-wing, or the Liberals, have not been able to sort of gather at all. The other quick limited point that I also want to make is that I think there's a sense of fierce ideological commitment that I don't see on the other side, that I don't see among the Liberals. With these guys, often they're not making money, oftentimes they're not really earning very tangible things out of doing this work, but they do it because they're so ideologically driven. I'm unsure if we see that kind of dedication and determination on the other side. I think sometimes we all very happy fighting in our little WhatsApp groups and walking out of a WhatsApp group and thinking this is my Revol of the day and I'm done, right, whereas a Kavi will go on and write a song about it and get millions of people to see it.

Answer to Dilip's Question on developing a counter-narrative:

So, there's also that difference because, in my view, the counter to all of this is to reiterate the values we've always stood for and the values we've somehow taken for granted, right? I remember growing up in school, there used to be these things saying Hindu-Muslim unity in diversity and so on, and I would keep thinking that, you know, why do we need to repeat this, of course, Hindu-Muslim unity, but now 30 years later, 35 years later, I see why it was necessary to reiterate that, except that I think people like me and maybe some people in the room, I think we all started taking these values for granted.

Kunal’s book is now available in bookshops across India, and you can get your copy on Amazon in other parts of the world.